On December 27, 2020, the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 (CAA) was signed into law. As one of the largest spending measures ever enacted by the federal government, the CAA combined COVID‑19 stimulus relief with regular annual budget appropriations. The CAA included the following three graduate medical education (GME) provisions, making it the first significant GME expansion opportunity in more than two decades:

- New reimbursement for 1,000 additional residency slots over five years (Section 126)

- Expansion of funding for rural training programs and urban-rural partnership opportunities (Section 127)

- Opportunities to reset hospital FTE caps and per resident amounts (PRAs) (Section 131)

On May 10, 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued the proposed FY 2022 Medicare Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment System rule. While this rule largely focuses on inpatient hospital payment changes, it also includes proposed policies for implementing the GME provisions in the CAA.

Below is a brief overview of the proposed rule, as well as considerations for healthcare leaders as they prepare responses to the call for public comments, which are due by 5 p.m. on June 28, 2021. [1]

New Reimbursement for 1,000 Additional Residency Slots (Section 126)

In order to implement the provisions of Section 126, CMS further clarified the eligibility criteria for hospitals to apply for additional cap slots by:

- Documenting which states qualify as those with new medical schools and/or branch campuses.[2]

- Recommending that hospitals must attest that more than 50% of resident training would be spent at locations within a mental health and/or primary care Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) to qualify for prioritization.

Because demand for additional slots will far outpace supply, CMS proposed limiting the maximum number of slots a hospital can receive to 1.0 FTE per year (a significant reduction from the original legislation). CMS also proposed two options for distributing the slots:

- In the first approach, CMS would prioritize hospitals supporting underserved populations and use HPSA severity scores (over the other three categories’ criteria) to distribute slots.[3]

- In the second approach, CMS would give higher priority to hospitals that qualify in more eligibility categories for FY 2023 only and further refine the distribution criteria with stakeholders for future years.

Opportunities for Public Comment

There are several issues that teaching hospitals may find warrant additional discussion and adjustment related to Section 126.

- The proposed distribution processes do not prioritize high-need specialties. This is inconsistent with the distribution criteria provided for cap redistribution in accordance with Section 5506 of PPACA. A similar process should be considered that emphasizes the specialties that are most acutely needed to meet the future healthcare needs of this country (e.g., primary care, mental/behavioral health) instead of potentially allocating slots to subspecialties with more limited need.

- Relying on the HPSA severity score (over the eligibility criteria of the other three categories) to distribute the slots disproportionately favors category four. We believe it was the intention of the original legislation to allow hospitals within one of the other three categories (that do not necessarily qualify within category four) to also be eligible for an award, and thus the distribution criteria should be reevaluated. As noted above, criteria for the other three categories may include factors such as community need for a particular specialty and/or demonstrated ability to support diversity in the physician workforce pipeline (e.g., through documented recruitment and retention statistics), which are impactful and should not be overlooked.

- Reducing the maximum number of available slots to 1.0 FTE per hospital per year effectively negates the opportunity to establish a new program, which is one of the prioritization categories. An award of 1.0 FTE would not be financially sustainable, as most GME programs require at least 3.0 to 5.0 FTEs to responsibly add one new trainee to each class year. Rather, we suggest that the proposed rule be revised to revert to the maximum award as originally included within the legislation.

Expansion of Funding for Rural Training and Partnerships (Section 127)

The proposed rule reaffirms the intention of the legislation to allow cap expansion at both the urban and rural hospital participating in a joint training program. It further clarifies that every time an urban and rural hospital partner to create a rural training track (RTT), both hospitals can receive a cap increase if certain conditions are met, even if the RTT does not meet CMS criteria for a “new program” (e.g., new residents, program director, and faculty; different clinical and didactic curricula). Notable elements of the proposed rule include the following:

- If a new RTT is created within an existing GME program that does not already have an established RTT, both the urban hospital and rural hospital may expand their respective caps to accommodate the new RTT.

- If a new “spoke” is created within an existing RTT after October 1, 2022 (i.e., a new rural site is added to the RTT with the same urban hospital partner “hub”), the urban partner and the new rural partner can expand their respective caps.

Opportunities for Public Comment

The proposed rule explicitly states that existing spokes within an RTT cannot receive additional caps, while new spokes are eligible, which disproportionately favors expansion into new areas over growth in existing RTT spokes. If the goal of Section 127 is to expand training programs in rural areas, then it should not discriminate as to which rural areas experience growth. Otherwise, urban hospitals will likely be forced to prioritize new partnerships instead of working with existing partners to build upon the foundation of their already established programs.

Opportunities for Resetting Hospital FTE Caps and PRAs (Section 131)

The proposed rule offers several points of clarification for implementation of hospital FTE caps and PRAs, as follows:

- Thresholds and hospital FTE counts to reset the PRA and/or cap will not be subject to rounding.

- CMS suggests that if a hospital enters into a Medicare-affiliated group agreement and trains less than 1.0 FTE, a PRA will be set, as the agreement is viewed as a representation of the hospital’s conscious decision to engage in teaching. However, if there is no Medicare-affiliated group agreement in place, the hospital does not set a PRA until it trains at least 1.0 FTE.

- If a hospital is eligible to reset its cap, the first year of any new program would serve as the base year for the five-year cap-setting period, which is consistent with existing regulations. However, CMS clarified that only new programs that begin training residents after December 27, 2020, would be counted in the newly established cap.

Opportunities for Public Comment

Below are items related to Section 131 that require further clarification.

- Regarding the PRA, the proposed rule offers no additional detail for hospitals that may have a presumed low/zero PRA (e.g., those that have trained a de minimis number of residents from existing programs in the past and may have inadvertently trigged a PRA but do not have formal, written determination or confirmation of such from their MAC). We suggest that such hospitals be considered as having no PRA for CMS purposes, thereby making them eligible to set an initial PRA after training at least 1.0 FTE following the date of CAA enactment (i.e., after December 27, 2020).

- For parity purposes, for hospitals with established caps that have started new training programs prior to December 27, 2020, but are still within that individual program’s initial period of years as of the date of CAA enactment, we suggest that they be eligible to expand their cap for that new program as well.

Action Items

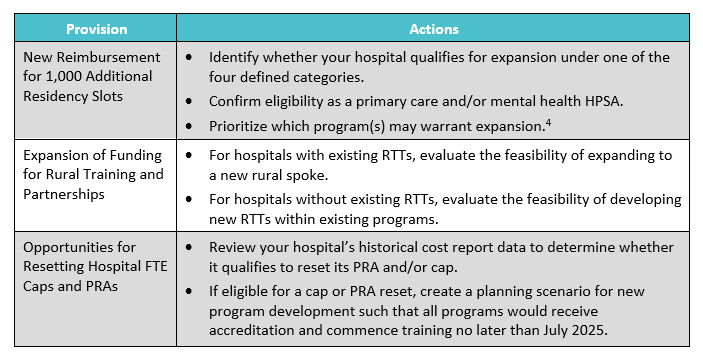

While the final rule may ultimately differ from the proposed rule, there are critical actions teaching hospitals can take now in preparation to capitalize on these GME provisions and expansion opportunities (see table 1).

Opportunities

Footnotes

1. Instructions for submission can be found in the Federal Register (Vol. 86, No. 88, Page 25070).

2. States or territories with qualifying new medical schools and/or branch campuses include Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, Nebraska, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Puerto Rico, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

3. The CAA outlined four categories of hospitals that may be eligible for additional cap slots: (1) rural hospitals, (2) hospitals in need of cap relief, (3) hospitals in states with new medical schools and/or branch campuses, and (4) hospitals located in designated HPSAs.

4. As noted above, given that the maximum award has been potentially reduced to 1.0 FTE, it is highly unlikely that developing a new program would be financially feasible without significant incremental hospital investment.