The growing pressure on hospitals to acquire physician practices often evokes memories of the primary care acquisition frenzy of the 1990s. Back then, staggering financial losses frequently resulted in divestiture, with little strategic gain for anyone. Physician employment is again at center stage, and this time it appears here to stay. The demands of payers, the government, and consumers to provide better care more efficiently will make economic integration between hospitals and doctors a necessity in most markets. Hospitals must find ways to build and sustain a network of primary care and specialty providers if they are to remain competitive over the next decade.

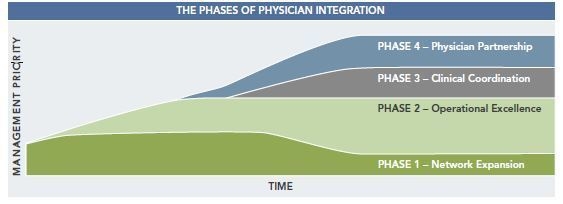

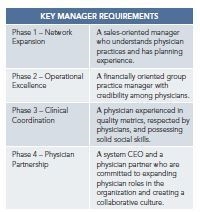

Attaining meaningful integration with providers is no easy task. The complexities involved, as well as the tools required to making integration initiatives successful and sustainable, require both clear vision and sophisticated expertise. Among the most important lessons is matching the management of the employed physician network to the changing needs of the network over time. Specifically, there are four overlapping phases of integration – Network Expansion, Operational Excellence, Clinical Coordination, and Physician Partnership. Each phase requires different management skill sets and priorities. Too often, hospitals fail to recognize the need to change priorities, and even managers, as a physician network grows and evolves. This article focuses on the phases of physician integration and discusses the management skills that are most appropriate to each phase.

The Phases of Physician Integration

As depicted below, there is a clear progression of management needs, which are dictated by the maturity of the physician network. For the majority of hospitals, the first priority is network expansion (physician recruiting). Then the focus should move to developing operational excellence, followed by the implementation of clinical coordination, and finally, developing a partnership that incorporates physicians in all aspects of system operations and governance. Hospitals that do not recognize the changing demands of the network or that are unable to work through the layering of management skills are likely to face significant barriers to success.

Phase 1 – Network Expansion Priorities: Marketing, Sales, and Planning

Most commonly, hospitals’ early acquisitions are opportunistic purchases of primary care practices, key specialists who are close to retirement, or practices in need of financial rescue. Hospitals frequently scoop up the practices with the intent to figure out the best ways to grow and manage the network at some future date. This acquisition phase is both necessary and appropriate, as a fully developed network takes time and collaborative effort to create. Regardless of the initial reasons to employ physicians, as hospitals move forward, the reality is that the competitive environment and payer requirements get more complex, and the pressure to grow the network intensifies. Whether it involves primary care physicians or specialists, hospitals cannot let their admitters be recruited by competitors and must bring needed providers and services into the network. Growing a network entails marketing and sales, although it is not often thought of in those terms. Physician interest must be piqued, a mutually agreeable terms sheet created and agreed upon, descriptive and legal documents developed, and many meetings held before the “sale” can occur and a physician or group of physicians can make the commitment to join the hospital’s network.

Unfortunately, many hospitals get stuck in this phase for long periods. Hospitals commonly add providers based on availability and give little thought to how these providers will improve efficiency or coordination of care within a given network. During Phase 1, hospitals should develop a well-thought-out plan codifying a number of objectives, including:

- The number of required specialty(ies) and timing for the recruitment of new physicians.

- The organizational model for the employed physicians.

- The deployment of employed physicians across the hospital or health system.

- The amount of capital investment required to fund the physician organization.

Rather than reacting to opportunities as they arise, hospitals can be proactive in building a network that responds to its strategic priorities, such as strengthening specific service lines or building satellite facilities, as well as preserving relations with independent providers. It is also critically important that the board, hospital leadership, and other key stakeholders understand how this plan supports the goals of the enterprise as a whole. While events will undoubtedly require adjustments to the plan, it is important to get consensus regarding the scope and likely cost of the network.

It should be recognized that clinical integration is different than economic integration.

Management must be focused on meeting with physicians, explaining the proposed arrangements, negotiating acquisition and compensation, overseeing the on-boarding process, and facilitating the creation of a physician network strategic plan. Based on the required tasks, sales, marketing, and planning, a high level of experience is critical to the network expansion phase.

Phase 2 – Operational Excellence Priorities: Practice Management, IT, and Compensation

After the initial rush to grow the physician network, attention invariably turns to how to efficiently manage the network. This frequently happens when the financial drain of the practices reaches a level that the hospital or system deems unsustainable. While the physicians are now employees of the system, it is often the case that the practices are not well organized or aligned within the system. In some cases, large guaranteed compensation agreements are in place and physician practice management capabilities have not been built. It is not surprising that in these situations the practices are not financially viable, nor is the physician network able to achieve its strategic goals (if goals have been identified).

The most expeditious way to overcome this hurdle is to transition as quickly as possible into operational excellence, the second phase of physician employment. In this phase, the physician enterprise develops its administrative core and builds skills around managing the practices, while continuing to grow the network. Hospital management often underestimates the specialized skill set needed to direct this process. Given the inherent complexity of leading a medical group within a hospital or health system, we believe the following are the most critical elements to focus on in order to ensure success:

- Providing ambulatory care IT infrastructure.

- Implementing EHR and practice management systems.

- Ensuring effective billing and revenue cycle performance.

- Negotiating managed care agreements.

- Standardizing policies and procedures.

- Monitoring physician performance and behavior.

To be effective during this phase, leadership must have credibility with the physicians and experience in managing group practices. It is important for managers to be able to continually engage physicians in maintaining focus on operational improvement opportunities while allowing the physicians to build and strengthen their clinical practices. Hospitals and medical groups compete for the limited pool of people with appropriate experience, but a seasoned practice manager is essential at this point if the network is to operate efficiently.

Administrators and financial managers will serve in supporting roles to ensure that clinical decisions are sustainable.

Phase 3 – Clinical Coordination Priorities: Physician Leaders and Care Coordinators

The ultimate goal of physician acquisitions is enhanced coordination of care and integration across the care continuum. The sad reality is that most providers currently share very little clinical information with each other. Diagnostic and/or therapeutic information from one location or encounter is often unavailable to others who treat the patient at another location. In developing a physician network, the coordination of care is too often deferred until “later” because physicians and management are not comfortable with how to proceed.

First, it should be recognized that clinical integration is different than economic integration. Clinical integration requires different operational activities and decision-making approaches than those of typical hospital systems. It should start with the integration and coordination of key services lines or programs. While integration often begins with primarily inpatient-focused services, the concept should be extended into ambulatory care and include a broad spectrum of providers and facilities.

Creating an integrated system means combining two types of businesses into a single healthcare enterprise.

In spite of how difficult it is, a transformation from traditional isolated care delivery models to coordinated care models is required if the hospital is to remain successful. This transformation cannot be done exclusively by healthcare administrators. Most importantly, the skills required focus on:

- Making clinical decisions.

- Evaluating evidence-based medicine protocols.

- Communicating clinical standards and expectations.

- Evaluating provider performance.

Leadership must come from physicians who are supported by clinical coordinators. Phase 3 therefore requires the addition of a different type of manager, as physicians and nurses become central to decision making. Administrators and financial managers will serve in supporting roles to ensure that clinical decisions are sustainable. When structuring leadership for clinical coordination initiatives, the balance of administrative and medical perspectives is an important goal. There are many ways to structure a leadership team that includes physicians, nurses, and lay administrators, but we have found that a “dyad” management structure, which pairs a physician leader with a senior administrator, can be an effective option for managing clinical coordination.

With the growing importance of clinical coordination throughout the hospital industry, it is not surprising that qualified physicians and care coordinators are in short supply, but these are the professionals needed to make any sustainable progress in reducing costs and improving quality in Phase 3. The search for physicians and nurses who will provide the needed clinical coordination leadership should begin very early in the integration process, whether those physicians and nurses are homegrown or recruited from the outside.

Phase 4 – Physician Partnership Priorities: Delegation, Communication, and Negotiation

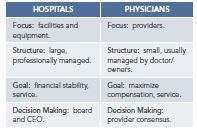

Virtually all hospital integration initiatives include physicians in administrative capacities (e.g., medical director) and the formation of a physician advisory committee to ensure doctors are included in at least some of the decision-making processes. While necessary and important, these limited roles must evolve over time into a true partnership, with physicians being embedded in all financial, clinical, operational, and strategic aspects of the integrated network. Creating an integrated system means combining two types of businesses into a single healthcare enterprise. Establishing the physician partnership is the fourth and final phase of physician integration and involves sharing control and changing the historical culture for both hospitals and physicians.

This is more difficult than it appears, because hospitals and doctors frequently have very different goals and ways of operating prior to an affiliation. Although this challenge is not specific to those organizations moving from Phase 3 into Phase 4, it is important that administrative and medical leaders recognize the motivational differences in order to effectively align and move forward. Major differences in traditional hospitals and physician organizations include:

While the table above may be oversimplified, the point is that not only are these two cultures different, but neither is likely to be successful in managing a financially and clinically integrated healthcare organization alone. For management, the challenge is to master a new set of operating activities that will address all the inpatient and outpatient care of a larger and more clinically diverse population than hospitals or physician groups have served in the past. Addressing this larger scope of activity will require collaboration between physician leaders and administrators at all levels of management and governance.

The challenges in the physician partnership phase are not technical as much as political.

Governance structures that encompass physician partnerships will vary depending on the specific model employed by the hospital, but each model can accommodate sharing responsibility for decisions, including capital and operational budgeting, facility planning, and maintenance of accountability for performance. Although balancing authority and responsibility is the major concern in sharing control with physician networks, finding the right balance over time is the key priority of management in this phase of integration.

Negotiation and communication skills are needed, along with lots of patience. Moving forward, senior leadership, both clinician and administrative, must direct the process. In most cases, the CEO of the system should work collaboratively with the most senior and respected physician leader(s) to maintain momentum, identify additional potential leaders, promote partnership opportunities, and plan for future enhancement of the integrated network.

The challenges in the physician partnership phase are not technical as much as political; that is, how to promote acceptance, collaborative effort, and eventually trust between and among clinical and administrative managers.

Talents Needed in the Four Phases

It is clear that successful physician integration takes much more than appointing an executive director and monitoring his/her activity. Rather, network expansion requires a layering of skill sets:

It is often possible to find a person who is capable of managing both Phase 1 and 2. The most frequent breakdown occurs when leadership lacks experience in practice management. Phase 3 proves the most challenging because a physician must develop an effective working relationship with a wide range of providers. Many networks get bogged down at this stage due to either a limited vision of care coordination or the lack of a suitable physician leader. Success during Phase 4 depends upon the willingness of senior physician and administrative executives and the board to promote and financially support the changes needed to create a fully integrated healthcare enterprise. At this point, many integration initiatives encounter conflict between their strategic goals and the entrenched culture of the organization. Integration requires commitment and focus to work through these conflicts and form the new culture needed to sustain an integrated delivery system.