In an effort to respond to changing dynamics in the healthcare environment, hospitals and health systems are finding themselves in the physician practice management business, much as they did in the 1990s. As with the earlier wave of acquisitions, there is often considerable pressure to get the deal done quickly; as a result, the focus of attention is often on the transactional, rather than the operational, components of the arrangement. Concerns such as asset valuation, legal documents and due diligence, and internal and external approvals dominate planning efforts, and the question of how to assimilate these practices into a cohesive physician network often gets short shrift. As a result, many hospitals are left with a mixed bag of acquired practices that function much as they did prior to their acquisition, with multiple billing systems and EHRs, disparate policies and procedures, and different ways of organizing and managing staff.

For the individuals who are tasked with managing the revenue cycle for these acquired practices, this scenario can become unmanageable quickly. As the network of employed physicians grows, so does the need for a coordinated billing operation with a common practice management infrastructure and consistent policies and procedures. This in turn necessitates tools, skills, and expertise in professional fee billing that are likely to be absent in both the acquiring hospital and the acquired practices.

Is It Really That Different?

Hospital executives will often say, “We do a great job of managing our own revenue cycle … how different can it be?” While it is true that there are common steps in both the professional and hospital revenue cycles (e.g., generate a bill, send it out, hope to get paid), the relative complexity of the professional process is significant, particularly in relation to the low amounts being billed. Industry benchmarks suggest that the cost to collect for the professional revenue cycle is nearly 2 to 5 times the cost to collect a similar return for hospital enterprises (i.e., approximately 4 to 10 percent of collections versus 2 percent of collections). Moreover, the cost to collect for physicians’ practices can vary dramatically, depending on specialty, payer mix, and accounting practices, so be careful in making comparisons to published benchmarks. Generally, surgical specialties are among those with the lowest cost as a percentage of collections, while primary care practices’ costs to collect are on the higher side.

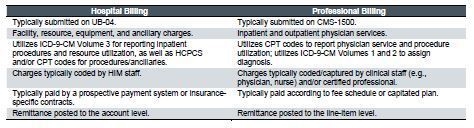

The table below provides an overview of some of the key differences between hospital and professional fee billing.

The complexity of professional fee coding (e.g., 7,500-plus CPT codes, 17,000-plus ICD-9 codes) and rules around reimbursement further compound the issue; even in an ideal scenario, it is often challenging to confirm whether the organization is being paid correctly. Coupled with the high-volume and low-dollar nature of professional fee billing, it is necessary to maintain a well-controlled process.

Why Does It Matter?

For many faced with this new responsibility, the temptation is often to focus on the higher-dollar hospital revenue cycle and to leave the newly acquired physician practices as they are. However, if the professional process is not managed effectively, billing costs will rise, collection rates will drop, and accounts receivable will increase to a point that the value of the acquisition is lost. There are other key considerations:

- Patient Impact – Patients’ billing experiences will affect the likelihood that they will return to that provider; this is true for both physician and hospital patients. However, there are typically more opportunities for patients to find alternative physicians than alternative hospitals. To that end, a mismanaged professional revenue cycle for acquired practices may lead to erroneous balances/statements, disparate standards and policies, and poor service, all fueling patient dissatisfaction and possibly attrition.

- Provider Impact – Providers’ level of knowledge and interest in the professional revenue cycle process varies significantly. Further, providers both affect and are affected by the process. Subpar controls and inconsistent policies can contribute to issues related to charge capture and collections, which can impact a majority of provider compensation arrangements we find in the market. Coupled with negative impacts to patient volumes (described above), poor revenue cycle performance can significantly damage hospital/provider relationships over time.

- Compliance – In its 2011 work plan, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) included a focus on evaluation and management services for the first time; this has carried over to the 2012 work plan, as well. This can create a great deal of risk for a hospital that has recently acquired physician practices, given that (a) providers are frequently involved in the coding of their own services, and (b) many providers coming from private practice are typically not well versed with compliance considerations.

Doing It Right

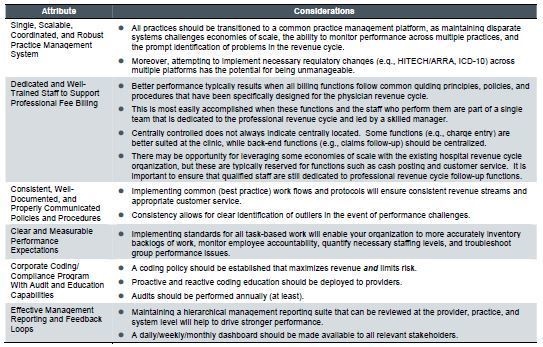

It has been our experience that the most effective professional fee revenue cycle models are scalable; improve financial performance; and support the organization’s mission, vision, and strategic initiatives. Key attributes of a successfully integrated model include:

Regardless of the rationale for acquisition (e.g., growth in market share, increase in downstream revenues, preparation for payment reform), the onus is on the acquiring organization to develop a consistent and coordinated billing model that can sustain or improve the organization’s financial performance throughout the changing healthcare landscape. As such, hospital leaders will need to think strategically about how they want to organize and manage this important piece of their business.