Hospital acquisitions of physician practices are often likened to a marriage, and for good reason. As in marriage, whenever hospitals acquire physician practices, both parties are in for some major changes – some anticipated, others not – that are sure to test the relationship’s strength. And regardless of the strength of the relationship, it is not one that can be easily undone. As a result, a healthy dose of commitment and compromise is required of the partners if the arrangement is to have any real hope of success. Unfortunately, in both types of relationships conflict inevitably arises, and things that they fight over are strikingly similar. For example:

- What to spend money on (particularly in times of scarcity) and who gets to decide.

- Perceptions that the other party isn’t pulling his/her own weight.

- Differences of opinion over major decisions that the two must make jointly.

- Perceptions that the relationship both parties got was not what they signed up for.

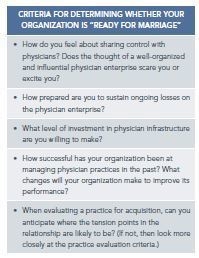

Sound familiar – at work or at home? While the above issues are common topics over which conflict arises, the root causes of conflict typically run much deeper and can usually be traced back to a lack of preparedness for the changes that the relationship will bring. Either that, or (more commonly) both parties lack the necessary skills, knowledge, or willingness to become “a couple” rather than two individuals bound only by a legal document and a common name and address. This can occur in many ways, such as naïve and unrealistic expectations, lack of “emotional due diligence,” or faulty preconceived notions about how the relationship should work. As anyone who’s experienced in these matters will tell you, these issues are not trivial and often receive too little attention during the courtship phase of the relationship.

It is not a stretch to say that hospitals and physicians often approach integration much like two naïve young lovers who are eager to be wed… or worse yet, two people in their forties who have been successfully single all their adult lives and think they’re pretty sophisticated, yet walk the aisle not realizing how much they still have to learn. Let’s take a look at how this plays out in the realm of hospital/physician integration and what to do about it.

A Mind-Set of “Me” Not “We”

Hospitals that are just getting into the business of acquiring and operating physician practices often forge ahead without first developing a clear vision of what they hope to accomplish and how to make that happen. In our experience, the most common mistake is failing to develop a strategy that redefines the organization as an integrated health system rather than a hospital-centric entity that just happens to employ physicians. When hospital executives and physicians enter the arrangement from a transactional, rather than a relational, perspective, the pre-acquisition discussions tend to focus on the deal terms and the operational considerations that are of immediate importance: financial analysis, asset valuations, disclosures and legal documents, compensation, exit provisions, lease and contract assignments, physician and staff on-boarding, and so forth. You might say they spend more time planning the wedding than thinking about their future together.

Obviously these things are essential, but they should not preclude more meaningful discussions about how the two parties can achieve greater success together than they could independently. Therefore, it is essential to dedicate sufficient time up front to addressing the things that will set the tone of the relationship and determine success in the longer term. For example:

- How will decisions get made?

- Which decisions reside with the hospital, which ones are at the discretion of the physicians, and which ones must be jointly made? In the latter event, who prevails in the event of an impasse?

- What are the expectations around communication?

- How do we blend two well-established cultures into a culture of “we”?

- How do we share governance of the new organization?

All of these questions need to be answered within the context of an integrated system and not a hospital-dominated system. Doing this will make the difference between a true hospital/physician partnership and an environment in which the physicians are dissatisfied, not engaged, and more than willing to share their woes with other physicians in the community.

Lack of Preparedness for Change

Having rushed into the relationship due to external pressures and without properly considering its implications, hospital leadership frequently underestimates the extent of change that integration entails. They may also lack the knowledge or experience to prepare for a significant organizational change and therefore assume that the benefits of integration will somehow occur in the absence of a well-thought-out plan. Of course, this is not realistic. Old habits are hard to break, and it will take time and effort in order to get a new, common culture to emerge, particularly when the group is composed of disparate physicians who are coming from private practice.

To ensure that this culture does emerge, hospitals will need to nurture and cultivate, rather than stifle, the physicians’ natural entrepreneurial spirit so that an engaged partnership can be created and maintained. For example:

- Create a structured communication plan so that physicians feel connected to the parent organization and to each other.

- Develop a sustainable plan to connect primary care physicians with specialists to enhance referrals.

- Develop a physician compensation plan that aligns the incentives of the physician with those of the parent organization. A significant portion of the physician’s compensation should be at risk, with hospital and physician group goals beyond just productivity as part of the plan.

- Set clear performance expectations and adhere to them.

The hospital’s leadership also needs to recognize that managing a physician enterprise requires a different skill set and perspective than managing a hospital, or even an outpatient department of a hospital, and behave accordingly. To achieve a more stable and successful partnership, the physician enterprise should not be regarded as a side business but rather as an integral part of the organization, on an equal footing with the hospital. The measures of performance that are relevant to physician operations are quite different from those of the hospital, and managers who have no background in medical practices are not likely to understand these differences right away. For example, when hospital managers are given responsibility for physician practices, they frequently impose hospital-oriented policies and procedures on the medical group, with a resulting increase in overhead costs. In most cases, it is necessary to hire new talent in this area.

An Ad Hoc Approach to Hiring

Lacking a well-constructed strategy for their physician network, practice acquisitions tend to be driven by events, resulting in a series of one-off transactions, each of which is unique and has inconsistent terms. One of the most common examples is the use of individualized (i.e., nonstandard) employment contracts, which introduce a variety of employment terms and compensation arrangements. This lack of consistency is soon discovered by the physicians, and divisions and dissatisfaction among them quickly ensue. All of this is particularly detrimental to efforts to build a cohesive group of employed physicians.

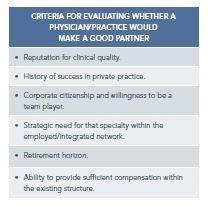

In many cases, the hospital ends up with practices it should never have acquired in the first place, because the implications weren’t properly thought through and/or because the lack of a standard approach and evaluation criteria makes it much harder to walk away when there is not a fit. This phenomenon can be mitigated by establishing criteria for determining whether there is a fit between the practice and the larger organization. These criteria need to be established in advance, within the context of a well-constructed plan, and without a particular acquisition in mind so that they will be untainted by the “tyranny of the urgent.” Of course, it is also essential to maintain the organizational discipline to abide by these criteria. To that end, it is helpful to document them in writing and refer to them faithfully before, during, and after every practice acquisition so that they are never forgotten or ignored.

Managing Physicians’ Expectations

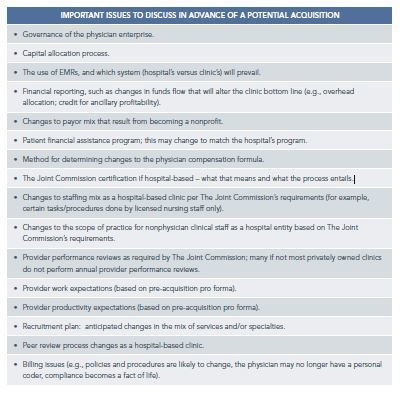

Another common problem is the failure to manage expectations from the outset. Physicians are often given the impression that little will change under the new arrangement, and the discussion about what it means to be an employed physician gets ignored. They then enter the relationship with false expectations, such as:

- They will retain the same level of autonomy they have enjoyed all their careers.

- The hospital will have no specific expectations regarding productivity or work schedules.

- All of the practice staff will be kept on the hospital’s payroll but under the physicians’ control.

- Compliance concerns will be no more burdensome than in private practice.

- The hospital’s superior access to capital will quickly “trickle down” to the physician practices’ projects.

- The EHR that they worked so hard to deploy will continue to be used in the integrated environment.

Of course, these expectations are unrealistic and will only result in disappointment. The way to avoid this is by being open and frank with physicians about these matters in the early stages of the discussion. Both sides should go out of their way to provide full disclosure of their future intentions and their old baggage.

For example, one of the authors experienced a medical group that informed the hospital after the transaction that its practice administrator had demonstrated a pattern of poor performance and misconduct for years, and that the hospital should do something about it. In another example, the hospital failed to inform the physicians that it intended to transition the clinic to a hospital outpatient department. Because of the governance and billing implications, this came as an unwelcome surprise. Maintaining full openness may be difficult when there is pressure to get the deal done, but addressing issues sooner rather than later will make life much easier for both parties and sets the tone for how issues should be resolved after integration takes place.

In some cases, it may make sense to schedule a facilitated retreat as a means of ensuring that sufficient time and attention is dedicated to developing a common understanding of how to live together.

Absence of Shared Governance

One of the mistakes that hospitals frequently make is the failure to tap into physicians’ knowledge and expertise and instead treating them as rank-and-file employees. While organizational charts may give the appearance of granting physicians a real say in how the enterprise is operated, ultimate power resides with the hospital. In an effort to appease the independent members of the medical staff (see the following section), employed physicians are often denied governance roles that could take advantage of their sense of ownership to create and drive strategy in a true partnership.

Medical Staff Reaction

In the absence of a clearly defined and properly communicated physician strategy, hospital executives often invite animosity from the independent members of the medical staff, who may perceive that the hospital is now competing with them. This can create a divide within the medical staff that is very uncomfortable for all, but particularly among the employed physicians. To appease the independent physicians, the hospital may find itself acquiescing to their demands, sometimes at the expense of the employed physicians. For example, the hospital may cancel plans to recruit in a given specialty that the newly employed physicians had planned to recruit. Hospitals may also find creative ways to shift money to the independent physicians via granting directorships, creating leadership roles, or paying for call coverage. While this may have a short-term benefit, it sets precedents that are very costly not only in financial terms but also in terms of the relationship between the hospital and its physicians, both independent and employed.

Hospital leadership should also be prepared to deal with negative behaviors that independent medical staff members sometimes exhibit when poorly prepared for the introduction of employed physicians. It is not uncommon to see independent physicians diverting poorly insured or uninsured patients to the employed medical group. In extreme cases, independent physicians can be openly hostile to the employed physicians, eventually driving them out of business by spreading false rumors or shutting them out of the call schedule. It is essential to gain the support of the medical staff leadership to ward off this type of reaction.

Conclusion

It’s often been said that your spouse is not the same person that you married. Of course that’s not literally true, but it feels that way to a lot of married couples whose real-life marriage experience is much different than they’d imagined during their courtship. Many health system executives and employed physicians experience that perception as well. While there is no way to anticipate and prepare for every challenge ahead, many of those challenges can be identified and addressed in advance. More importantly, having realistic expectations and a mutual understanding of how to deal with the unknown will go a long way toward establishing a successful and mutually rewarding integration of hospitals and physicians.