Since the days of physicians traveling the countryside to make house calls, access to health services has been a cornerstone of effective patient care. Actually providing readily accessible care to the entire population, however, is a goal that continues to elude health systems and physician groups. Expanding access to care and health information is a key priority of healthcare reform, value-based care, and population health management. In order to improve patient access, health systems and provider organizations must think beyond traditional care models and adopt innovative strategies in redesigning how, when, and where care is delivered.

Growing Discontent

Providers throughout the health system are doing incredible clinical work, and many patients receive timely, high-quality care. Yet when access to care in the United States is compared to other industrialized nations, our health system is consistently found to lag behind the leaders. The Commonwealth Fund’s annual report on how the U.S. healthcare system compares internationally often ranks the United States last, or near last, along specific measures of performance, including access. The average national wait time for an appointment with a physician is nearly 3 weeks. 1

Recent media coverage has highlighted access issues in healthcare. One example is the Veterans Administration scandal, whereby it is alleged that access-to-physician metrics were routinely falsified, making it seem as if veterans had better access to care than they actually did. Adding to the conversation, a recent Washington Post editorial argued that struggles with scheduling an appointment can often be attributed to technology systems that are as fractured as the health system itself. 2 Even if wait times were not an issue, more people have difficulty accessing care due to cost in the United States than any other industrialized nation.3

Not surprisingly, Americans routinely report issues making same- or next-day appointments for acute care, getting medical advice over the telephone, and receiving care beyond normal office hours. Access difficulties are met by a growing discontent among patients who are willing to switch providers or abandon traditional office-based care settings altogether in order to obtain the care they believe is necessary.

Expanding Access, Retaining Patients

Despite the technological means we have for communication and interaction, patient access is still primarily associated with face-to-face contact between patients and providers in the ambulatory clinical setting. While in-person encounters remain pivotal for effective, patient-centered care, there is plenty of evidence suggesting that the needs and expectations of patients are not being met by the traditional scheduling and delivery of care. Physician practices have long struggled with implementing efficient scheduling protocols, effective communication channels, and ideal work flows needed to broaden patient access. These problems are largely self-inflicted – many organizations employ a provider-centric gatekeeper model, whereby access to the caregiver is tightly controlled and too often confined to limited appointment availability, specific hours of operation, and the office setting. In some cases, physicians have impeded the expanded use of advanced practice clinicians (APCs), who could provide additional access points for patients. Providers also tend to shrug off routinizing procedures and protocols in ways that facilitate other licensed providers to increase their role in patient care. This has created multiple barriers and mounting frustration for patients.

Timely access to care is the factor most commonly cited by patients for why they select and remain with a provider or medical group; conversely, lack of access is the chief complaint reported by patients who switch providers. 4 This means that clinical competency is not the main determinant of why patients stay with a provider or leave the practice – accessibility is. And gaps in access have enabled a new wave of nontraditional competitors to enter markets and lure patients away from traditional settings with readily accessible, lower-cost, and more-convenient care options. Urgent care centers, retail clinics, subscription-based video consults, and phone- or Web-based nursing resources are emerging and attractive options for patients experiencing difficulty accessing care.

Losing patients due to an inability or unwillingness to remove barriers to care has considerable consequences. Financial incentives – and penalties – are being linked to an organization’s ability to attract and retain patients and effectively manage the health of the population. All of this is directly connected to accessibility of care. As patients become more proactive in managing their care and have more options to choose from, they increasingly expect to receive care when and where they need it. In turn, they demand greater access to providers within and across systems, as well as to health information and advice/treatment outside of the clinical setting.

Rethinking Patient Access

Provider groups are recognizing that the customary model of scheduling routine appointments weeks or months in advance and force-fitting “urgent” appointments into already overbooked schedules does not align with the tenets of accessible care or the expectations of patients. Provider organizations that successfully expand patient access through innovative strategies and across multiple points of entry will be best positioned to reap the operational and financial rewards that come from keeping patients within the system, enhancing patient satisfaction and loyalty, and differentiating themselves from the competition.

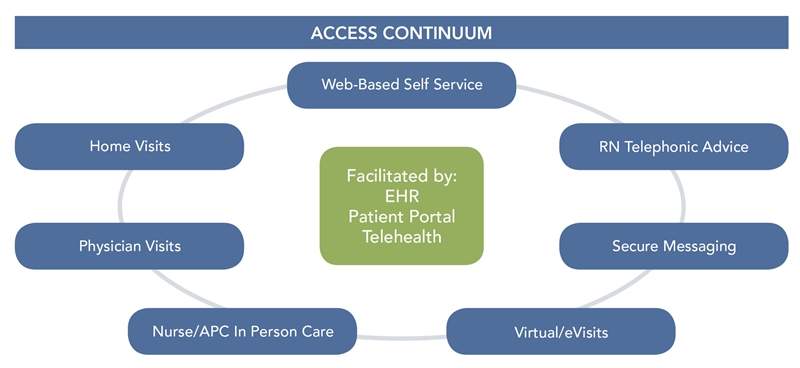

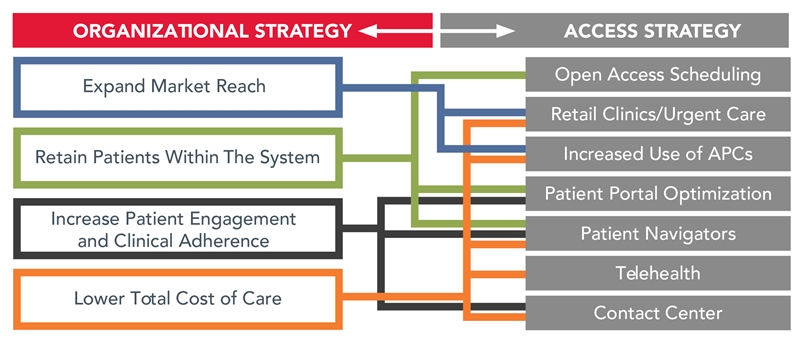

So, what strategies are organizations using to overcome operational challenges and improve patient access? Basic operational strategies include open-access scheduling and expansion of patient care hours, locations, and providers. The use of patient navigators, patient contact centers, patient portal optimization, and telehealth tactics are a few of the additional innovative strategies our clients are implementing.

Open-Access Scheduling. Goals of maximizing physician schedules so they are fully utilized, satisfying physician preferences, and offering patients care when they need it have been elusive. Open-access scheduling, which has been around for years, centers on the use of completely open schedule templates, few restrictions on appointment types, and the elimination of most future scheduling of appointments. However, many organizations that previously adopted pure open-access philosophies have had to modify this approach to add more scheduling structure in order to better meet patient and provider expectations. As such, a modified open-access approach may include limiting appointment types to fewer than five, standardizing scheduling rules within a specialty, and allowing future scheduling based on patient preference. This tends to improve both patient and provider satisfaction with scheduling while retaining the efficient components of the open-access model.

Expanded Care Settings and New Provider Types. Operational strategies related to patient access typically revolve around expanding hours outside of the traditional 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. time period, as well as employing allied healthcare providers such as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, social workers, and dieticians. Many organizations have expanded primary care hours in the evenings and on weekends to meet patient preferences and to compete with “convenient care” clinics. Similarly, health systems have begun to align with urgent care centers and even integrate them into their primary care networks. Partnerships between health systems and pharmacies that have in-store clinics, such as Walgreens and Rite Aid, are also being forged. While a PCP-focused model is often esteemed as the pinnacle of coordinated care, using a combined primary/urgent care strategy often results in broader patient reach. After urgent care patients enter the system they can be redirected to primary care, resulting in increased patient capture rates.

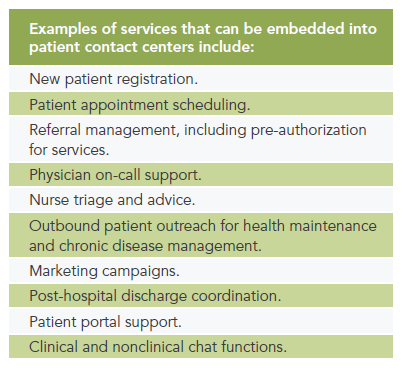

Patient Contact Centers. Patients face numerous restrictions when attempting to contact caregivers via telephone (i.e., limited hours, having to leave messages, phone tag). Once reviled as the antithesis of patient-centered care, organizations are turning to comprehensive contact centers (either insourced or outsourced) to manage the increasingly complex business of efficiently getting the patient connected to the right provider. Patient contact centers are capable of housing a broad range of services, including clinic operations, post-acute coordination, clinical services, and e-Care facilitation. Ultimately, when utilized effectively, these contact centers can provide both clinical and nonclinical support to patients, telephonically as well as virtually. Our clients with more than 100 providers have found that contact centers can answer patient telephone calls more expeditiously and achieve greater levels of service than in situations where telephone traffic is decentralized at each clinic. In addition, we have found that contact centers that include referral coordination experienced reduced denial rates and patient leakage, contributing to real financial gains.

Patient Portal Optimization. Patient portals have been available for years, but health systems are just beginning to use them to engage patients directly. Common portal features include: secure e-mail correspondence between the care team and patient; direct online appointment scheduling; and access to lab/test results, prescription refill requests, and visit summaries. Innovative organizations also leverage portal technology to gather information on patients’ medical, family, and social history, as well as to conduct pre-visit health risk assessments. Portals allow patients to take a proactive role in managing their healthcare, resulting in potentially more effective prevention strategies and reductions in unnecessary visits. They also give patients a level of access to their information that they have enjoyed for years in other industries, such as banking and insurance. In working with clients to implement and optimize their patient portals, we find that any concern about allowing patients real-time and/or complete access to their medical records typically gives way to trust in their patients’ responsible use of the information.

Beginning in 2014, all stages of meaningful use require this type of activity and incentivize organizations that utilize patient portals and encourage patient engagement. The return on investment from patient portals is evident in the reduction of telephone calls and related paperwork, not to mention postage savings associated with mailing paper-based communication. These benefits are in addition to other harder-to-measure but very tangible returns, such as cost savings from reduced hospital readmissions. It is not a coincidence that organizations with more concentrated managed care (e.g., Kaiser) were early adopters of patient portals.

Patient Navigators. Patient navigator programs are aimed at guiding patients through the convoluted healthcare system and providing an optimal experience. In their most advanced form, navigators are similar to case managers who help coordinate every step along the care continuum, including both administrative and clinical components. They may find the appropriate providers and schedule appointments, coordinate the transfer of health information among providers, educate patients about next steps in a treatment plan, provide after-hours support when physicians and/or clinic staff are unavailable, and empower patients to take a more active role in their care. In our experience, patient navigators are most commonly used in patient-centered medical home models and for specific conditions, such as cancer, that require access to multiple specialists.

Investing in the personnel required to perform these functions has traditionally been associated with chronic care populations, specifically those for which organizations accept financial risk, as these investments keep patients out of the hospital (and loyal to the organization). As other value-based payment initiatives proliferate, organizations are more open to investing in patient navigators to improve both patient access and care quality.

Telehealth Strategies. Telehealth programs range from technically sophisticated e-ICU monitoring systems to pay-per-use primary care visits via video conferencing technologies, such as Skype. Increasingly, organizations are recognizing that scheduling an appointment 3 to 6 weeks in the future is not acceptable or adequate for many conditions. The market is being flooded with non-conventional solutions that provide easy access to medical advice for acute, same-day needs through telephone and Web portals. Both health systems and nontraditional provider organizations (e.g., CareSimple, Carena) are offering subscription membership plans, as well as one-time services at a flat fee.

While there are concerns about these services replacing “true primary care” (similar to concerns expressed about urgent care centers 10 years ago and retail clinics more recently), the reality is that the market is demanding quick, easy access to care for a reasonable price. If health systems cannot meet this consumer need, other organizations will certainly fill the void. Once again, traditional fee-for-service reimbursement is a barrier to expansion of telehealth, given current CMS guidelines. However, CMS is increasingly considering reimbursing providers for patient care-management activities not involving face-to-face contact. 5 Our clients who have successfully implemented primary care-based telehealth programs have found that a combination of 1) modest subscription fees and 2) ensuring that all clinical personnel are working at the highest level of their licensure can ease the financial disincentive to provide virtual care.

Answering the Patient Access Imperative

The fact that patient access problems have long plagued healthcare delivery systems is a clear signal that the traditional ways of delivering care are ineffective at meeting the health needs and expectations of the population. The often used maxim applies here: “if you always do what you’ve always done, you’ll always get what you’ve always got.” As healthcare evolves, so too should the ways care is accessed and delivered. Yet, successfully expanding access requires more than good intentions and hard work. Efficiently and effectively addressing the health of the population and remaining competitive in the marketplace requires healthcare organizations to proactively pursue and embrace innovative strategies for expanding access to health services.

Footnotes

1. Merritt Hawkins & Associates, 2014 Survey: Physician Appointment Wait Times and Medicaid and Medicare Acceptance Rates.

2. Tsukayama, Hayley. “Why it’s such a headache to schedule a doctor’s appointment,” Washington Post, June 30, 2014.

3. Davis, K., Stremikis, K., Squires, D., and Schoen, C. Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: How the Performance of the U.S. Health Care System Compares Internationally, June 2014. The Commonwealth Fund.

4. Improving Patient Access to Care, 2002, The Dartmouth Institute.

5. Robeznieks, A. “The Right Direction,” 2013, Modern Healthcare.