Developing integrated, value-based care delivery models requires unraveling existing systems and processes and weaving together new ones in new ways. It’s an uncomfortable, disruptive effort with few guidelines, and most hospitals and health systems in the midst of it are finding it messy and complicated.

The reality is that many will fail. Mergers and acquisitions to build scale won’t be enough to meet population health goals. Integrated care solutions call for larger, fiscally strong health organizations—not necessarily with shared balance sheets—to partner with one another and with other area providers to jointly develop systems of care that offer value-based solutions.

Difficulties typically arise when goals lack focus or there is a reluctance to challenge current clinical processes and physician-

referral patterns, and success won’t be dictated by who is involved or the structure and process they use. Ultimately, it will boil down to who can actually put these symbiotic relationships together—integrate cultures, technologies, geographies and financial circumstances—then deliver results and get paid for the value of these results.

Untangle the Value Conundrum

Two of the biggest issues a partnership must clarify relate to value: How will the network define value, and how do participants equitably distribute the value that is created among the participants?

The answers form the framework onto which all other relationships are woven.

Getting agreement among partners about how to define value creates a framework for these new partnerships and prioritizes goals. Is the partnership about making care more efficient? Making care safer? Improving outcomes? Reducing costs and waste? Succeeding on a risk-based contract?

An even more challenging aspect, which few have answered, lies with the potential monetary return on the investment. How will financial returns be generated? Will they be distributed equally among hospital and physician partners? When, and in what magnitude?

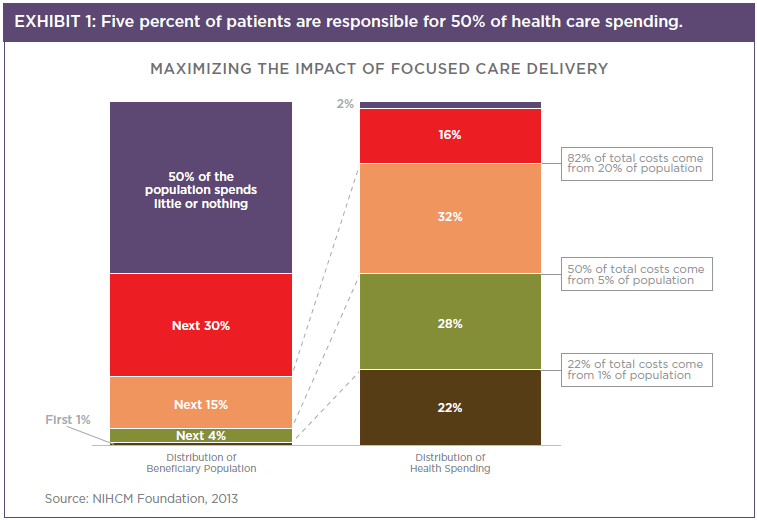

One clinically integrated network approached this by unraveling its existing care system and refocusing on the 10% of patients generating a disproportionate share of the insurer’s health care costs. They made behavioral health services a critical component in the care of these patients and estimated that more effective care management would reduce the high users’ total spend from $9 million to $6 million. The $3 million savings generated will be split equally between the health system, the independent physician association partners and the insurer.

Besides defining how value will be distributed among partnership members, this network was also strategic in targeting a very specific population health goal. Narrowing the network’s focus as much as possible in the beginning can help mitigate some of the early risks and help the entity achieve measurable value. (See Exhibit 1.)

Tighten the Weave

Partnerships by nature are looser arrangements than mergers or acquisitions, making them flexible, but also prone to fraying if they’re not carefully constructed. Each partner must be well integrated into the overall design so the structure retains its integrity in the face of difficult decisions and inevitable challenges.

For organizations that want to start slower, staging the partnership can help ease everyone in. For example, the health systems and physicians in one new arrangement began by self-insuring their own employees. Initially, they share only “upside” savings (upside risk) as the physicians and the evolving clinical processes are tested and evaluated for success. All parties know that within two to three years they will move together toward accepting both “upside” and “downside” risk for caring for this specific population of employees and dependents.

Keep in mind, however, that partnerships aren’t always equitable societies, so the ways in which individual partners come together may have to vary. Smaller providers and critical access hospitals, for example, won’t necessarily have the same level of capital to invest in a partnership as a major health system, but may be essential components due to geographic location or strategic interest in changing care. There must be alternative options available for these organizations to have “skin in the game” without the same level of financial commitment or risk. In turn, it will be necessary for these differential partners to accept certain trade-offs, such as serving on a committee rather than holding a board seat. Outlining these criteria from the outset will not only set out participation expectations and help entities commit beyond the initial investment, but will also help all parties better understand how risk will be balanced across the network.

Ensure Expertise and Interest Govern the Group

A new entity formed by multiple parties is typically governed by a body representing all of those who invested, with local physicians also participating. But this typical approach will not work here. If these partnerships are established on the belief that dramatic change in the delivery and cost of care needs to happen, then governance expertise must trump or be equal to investment when it comes to governing.

This is a particularly sensitive spot for partners because it means giving up representative board seats, and that creates discomfort. But to succeed in unknown territory, in an area where the partners lack real expertise, partners must be willing to give up some of their governance control and be open to leadership guidance from experts from other parts of the health care field who have been down the road before.

To identify the right board mix, the partnership must be crystal clear in what it’s trying to achieve, then seek out leaders with specific expertise. In some cases, this may require changing board bylaws to accommodate non-local or otherwise non-traditional board members.

In one PHMO, the founding and investing partners relinquished several board seats to add needed expertise, including a retired insurance executive who had served as CEO of a statewide insurer and the medical director of a large East Coast independent- physician association. Adding this level of expertise changed discussions and challenged the organization’s goals, raising difficult but essential questions that aren’t normally heard at health system board meetings.

Physicians too must play a significant role in the partnership’s efforts to improve clinical care. In another uncomfortable truth, partners must recognize that traditionally hierarchical physician relationships must bow to the higher purpose of alignment and integration. Physician seniority must weigh less than interest in and engagement in the process. Some partnerships have successfully pulled in the right physicians by creating a job description that details the skill set and time dedication necessary, then interviewing physicians across the organization. As the job typically requires physicians to spend substantial time away from their practice, reasonable compensation is important. In some cases, compensation can run upward of $300 to $400 per hour.

Visualizing the Population Health Tapestry

We’re at merely the beginning stages of changing the health care delivery system, so it will be some time before a clear image of fully integrated delivery systems emerges. These partnerships will be the flexible yet multidimensional bases of the future care paradigm and future physician and hospital revenue streams. Those that succeed will have unraveled a broken, fragmented system and created a new one, weaving in both old and new delivery platforms with both old and new leaders to truly disrupt the market, their own organizations and patient outcomes.