The emergency department (ED) is the last-resort healthcare provider for many Americans, yet 5% of ED patients account for 25% of all the visits,1 and 62% of all ED visits are for avoidable conditions.2, 3 The population frequenting the ED for nonurgent conditions is known as “super utilizers” (SUs), and they each account for 10 to 20 ED visits per year, often across multiple EDs. SUs are medically and socially complex patients who have extensive chronic conditions, which may be further exacerbated by social barriers and behavioral health conditions, including mental illness and substance abuse disorders. 4 A recent study published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) indicated that in 2010 the top 1% of patients ranked by their healthcare expenses accounted for 21.4% of total healthcare spending, at an average annual cost of $87,570, 5 a figure that lends further support to the value of intervention.

Although the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was generally expected to lead to declines in ED use amid increased health insurance coverage, volumes have actually continued to climb. Between 2012 and 2013, the nation’s 24 busiest EDs reported an 18.7% increase in visits. Medicaid recipients may have a particularly hard time finding physicians who will accept their coverage, or they may encounter excessive wait times for primary and specialty care, both of which can result in the use—and often reuse—of the ED for conditions that are often better treated in the primary care setting.

As payers shift away from fee-for-service (FFS) to value-based reimbursement, EDs have a greater incentive to control unnecessary use. Under value-based payment models and shared-savings programs, ED visits are reimbursed at a reduced and/or pre-negotiated FFS rate and ED providers are omitted from gain-sharing arrangements. From the perspective of hospitals, payers, and patients, efforts to address ED overuse are imperative. In response, there is a growing interest across in programs designed to curb ED visits by SUs across the public and private sectors. And new funding opportunities are emerging to support these programs.6, 7

MISSING THE MARK

Successful approaches to stem ED super utilization must go beyond the ED, traditional care models, and social service paradigms in order to fully address SU needs and make lasting changes to patterns of care seeking and health outcomes among the existing SU population. Primary care physicians (PCPs) and ED physicians may have limited resources and availability to fully combat the spectrum of social and medical complexities that impact an SU; the nonmedical needs of SUs (e.g., residence in a food desert, lack of access to reliable transportation, financial challenges) can be especially difficult to address in a routine office or acute ED visit. Even traditional care management approaches that are integrated into primary care—such as reliance on claims data to assess historical utilization and phone-based outreach and support—have limited success in meeting the needs of many SUs who need one-on-one intensive outreach and intervention.

Other efforts to disincentivize the overuse of the ED include greater cost sharing between the patient and payer, including increased ED co-pays. From a healthcare quality perspective, studies have shown that elevated cost sharing reduces the use of outpatient services, including appropriate office visits and preventive care. This can produce adverse effects on patient health outcomes, which may lead to the exacerbation of existing chronic conditions.8 It is well documented that cost sharing impacts care-seeking behavior, which further reinforces the need to design SU interventions that incorporate factors beyond the ED.

DEFINING A STRATEGY

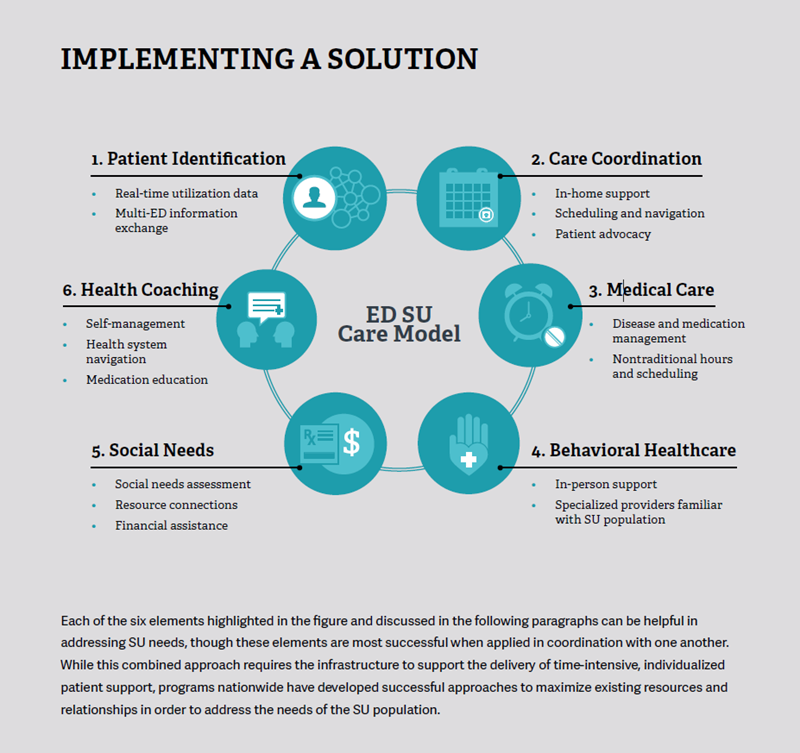

ED SU interventions should be designed to identify SUs; provide appropriate care to meet social, medical, and behavioral health needs; and provide monitoring and frequent follow-up. Interdisciplinary care management teams can address many of an SU’s medical and social needs by employing a combination of care coordination, in-person medical and behavioral care, assistance with social needs, and health coaching,9 with specific attention to gaps in care. From patient identification to health coaching and post-intervention follow-up, many aspects of the SU program can be performed by non-clinicians. This, in turn, helps to not only manage program costs but has also been shown to increase the level of trust built between the care team and the patient.10

Employing a multidisciplinary approach in population health efforts is not a unique concept, but demonstrated success in the ED SU population is limited and warrants a more focused approach. Intensive, short-term programs of 6 to 9 months that take ownership for an SU’s full medical and social needs have been shown to improve health status and behavioral conditions, as well as change patterns of ED use. Following successful intervention, patients are fully transitioned back to their care providers with stabilized health conditions and individualized care plans.11

1. PATIENT IDENTIFICATION

Identification involves the use of analytics to determine patients who meet an SU program’s inclusion criteria, which are most commonly tied directly to the number of annual ED visits. Claims data can be used to analyze the total cost of care, common diagnoses, and treatments for SUs, all in order to isolate factors impacting care-seeking patterns. By using claims data, a program that integrates components specific to the SU population can be designed. Unlike traditional case management programs, this data is not used to identify SUs in real time. The most successful methods to flag SUs once they present in the ED involve real-time data aggregation across hospitals to better inform providers of utilization patterns. Infrastructure such as the Emergency Department Information Exchange (EDIE) can provide regional data integration capabilities to enable intra- and inter-ED coordination. Systems like EDIE not only help SU program coordinators to more accurately identify SUs when they appear in any regional ED, but they also facilitate more cost-effective care delivery by reducing duplicative testing and procedures performed recently at neighboring EDs.

2. CARE COORDINATION

This component typically involves activities such as scheduling appointments, coordinating primary and secondary care, frequently checking in to ensure the care plan is being followed, and communicating with clients’ PCPs. SU care coordinators also ensure that a patient has access to necessary pharmacy and primary care, and they go beyond typical scheduling functions by using their familiarity with local community organizations and state agencies to help address any additional gaps, such as the lack of reliable transportation. A unique component of an SU program is the ability for care coordinators to provide in-home support. By meeting a patient in his/her home, greater trust is built, a relationship is established with the client, and the entire care team can more fully understand and address a patient’s social needs.12

3. MEDICAL CARE

SU medical care is centered on the delivery of in-person disease and medication management. To combat the lack of primary care support for most SUs, the development of a specialized clinic outside of a patient’s primary care setting dedicated to providing medical care and supportive services unique to SUs is favorable. Ideally, this clinic provides options for nontraditional primary care hours, such as open scheduling, same-day appointments, walk-in appointments, and 24/7 on-call access to providers. Unlike many traditional care settings, patients are not penalized or terminated for missed appointments, which further disincentivizes seeking care in the nonurgent setting. Providers develop individualized care plans for patients and deliver integrated physical and behavioral health stabilization treatment, with the ultimate goal of transitioning patients into effective primary care homes. While the medical elements of this approach can be embedded into a traditional primary care setting, in the ambulatory intensive care unit (ICU) setting providers can be specially trained to care for SUs and can dedicate the time and resources to deliver highly individualized, complex care.

4. BEHAVIORAL HEALTHCARE

Behavioral healthcare is a crucial element of any SU program, as SUs often have higher rates of mental illness. These services may include the administration of behavioral and addiction assessments, chemical dependency treatment, and mental health counseling.

5. SOCIAL NEEDS ASSISTANCE

SUs’ medical needs are often compounded by complex social needs, which can inhibit well-intentioned efforts to reduce ED utilization. Patients are administered a comprehensive social needs assessment to fully determine what barriers they face, if any. The program should be equipped to meet a variety of social needs, including assistance obtaining housing, transportation, food, and fuel, as well as financial aid for medication or other treatment needs.

6. HEALTH COACHING

Health coaching involves providing self-management support, medication reconciliation, and medication education, as well as teaching SUs how to navigate the health system. This approach gives patients the tools to successfully administer self-care and to preserve their health status once they are stabilized, which are both critical elements to changing care-seeking patterns.

FINANCING THE SOLUTION

Sustainable financing is crucial to ensuring that targeted patients receive care to fully meet their medical and social needs and to successfully change care-seeking behaviors. Typically, government and commercial payers, large public or private organizations that serve as healthcare purchasers for their employees, and hospitals that provide a large amount of uncompensated care have pursued these types of programs because they have strong financial incentives to mitigate the high costs incurred by the ED SU population. While SU programs have a significant cost avoidance component by cutting down on non-reimbursable services or decreased FFS reimbursements for ED visits, these programs are not typically profitable unless they receive grant support, case management revenue, or involve other cost-sharing or shared-savings agreements.

Financial reimbursement methods can be integrated in various combinations depending on the payer landscape, patient acuity, and subsequent scope of services provided. One option is a per episode of care payment for program services. In this scenario, the SU program would receive a payment directly from the payer for each episode for each insured individual. This payment covers all program costs for the specific duration and can be adjusted based on the complexity of the individual’s condition(s) as represented by a risk score (i.e., the individual’s cumulative number of medical, psychosocial, and behavioral conditions). Another financing option is a shared-savings plan for the total cost of care. Similar to a fully capitated model, payers enters into a partial risk-sharing arrangement with the SU program’s parent organization and share program savings over a fixed period of time.

CASE STUDIES

Various combinations of the programmatic and financial elements described in the following case studies have been successfully incorporated into SU programs nationwide to decrease ED super utilization and subsequent costs.

SPOTLIGHT ON SUCCESS

ST. CHARLES MEDICAL CENTER (Bend, Oregon)

In the first year of its implementation, the St. Charles Medical Center ED diversion project achieved a 49% reduction in the number of ED visits by SUs and reduced costs by an average of $3,100 per patient.13 Since then, it has continued to achieve positive results, reducing system-wide Medicaid ED visits by 32%.14

The diversion project’s multidisciplinary care team is composed of an ED physician, a nurse care manager, a social worker, a behavioral health consultant, and a nonclinical community health worker. Nurse navigators embedded in the program carry a caseload of 60 to 75 patients, while community health workers see panel sizes of 200 patients. Kristin Powers, Manager of Health Integration Projects at St. Charles Medical Center, described how the program invites “the entire care team to participate in identifying pain points so that the patient can make different choices and get their needs met.” Within the care team, nonclinical community health workers help patients navigate the healthcare system and have the unique ability to accompany patients to primary care appointments and advocate on their behalf if necessary. Powers explained that every SU “has some kind of motivation,” and a critical component of the program is working with the multidisciplinary care team to “discover what that motivation is and see if they can do something about it.” The care team specifically works to resolve barriers that prevent patients from accessing primary care in an outpatient setting, such as transportation, housing, or lack of phone service.

The program is reliant on EDIE, which helps St. Charles Medical Center see its patients’ real-time utilization and allows ED physicians access to existing care plans when patients present in the ED. The program receives funding through a shared-savings agreement with PacificSource Health Plans, a Medicaid plan, provided that the program meets previously agreed-upon outcomes, including lowering ED utilization in the target population and demonstrating high patient satisfaction in the services received. Robin Henderson, Chief Behavioral Health Officer and Vice President of Strategic Integration at St. Charles Medical Center, noted that while “it was not challenging to get local health providers, payers, and hospitals to financially support the shared-savings model,” it was surprisingly difficult to gather data to assess the program, since it came from both the state and health plan, even when working exclusively with Medicaid patients.

SPOTLIGHT ON SUCCESS

HENNEPIN COUNTY MEDICAL CENTER (Minneapolis, Minnesota)

Hennepin County Medical Center’s Coordinated Care Clinic was designed specifically to address SU needs and is known as the Ambulatory Intensive Care Unit. The clinic is on the same site as the ED and provides enhanced outpatient care to ED SUs. This program saw a 38% decrease in ED visits, a 25% decrease in hospitalizations, and a 23% decrease in per patient costs over the first year of participation. Patients are identified using a county-wide data system that integrates all information from the partner health plan and providers, which allows patients’ utilization patterns to be seen across facilities, so more informed care interventions can be developed.15

The clinic integrates primary care, behavioral health services (e.g., chemical dependency treatment, mental health counseling), medical treatment management, care management, and assistance to address social needs. Program participants receive formal medical, behavioral, and social assessments conducted by a medical provider, a nurse care coordinator, a clinic social worker, a pharmacist, and often a psychologist and chemical dependency counselor.16 Patients average 2.5 contacts with the clinic per month and typically meet with two to four members of the multidisciplinary team during a visit. To encourage clinic use instead of ED visits, the clinic accommodates all walk-in patients in addition to providing appointment-based care. Patient navigation and coordination is provided by clinic-based nurse coordinators and social workers. The program involves several regional players, including the medical center, a nearby FQHC, and a health plan, and employs a risk-sharing agreement. In addition, the health plan partner uses its Medicaid Managed Care per member per month payment to pay for data analytics and care interventions necessary for the program.

STRATEGIC BENEFITS

ED SU programs have the capability to decrease not only unnecessary utilization but also payer and hospital costs, as well as to improve patient health outcomes. Estimates suggest that eliminating unnecessary ED visits could save $38 billion 18 because of the significant cost differential between services administrated in the ED versus in the primary care setting. The case studies outlined above produced decreases between 38% and 65% in subsequent ED visits, as well as per patient cost savings ranging from $3,100 to $24,170.

Other ED SU program benefits include increased ED capacity for acute patients, hospital revenue, and primary care utilization; improved patient outcomes; and decreased uncompensated care charges and nonurgent ED use.19

OVERCOMING BARRIERS

Common barriers to implementing comprehensive ED SU programs are a lack of financial support and an aversion to taking on risk. As the healthcare system adapts to reform, insurers have a growing interest in funding ED SU pilots as a means to avoid costs. Shared-savings programs with both upside and downside risk potential have the capacity to encourage payers and providers to meet the needs of the medically and socially complex SU population.

As insurance expansion demonstrated, the increase in insured individuals seeking primary care was met by an inability for providers to respond. Provided that ED SU programs are successful and results are sustained, we should expect the demands for primary care to increase further, especially for the Medicaid population. In order to produce lasting effects, significant efforts need to take place to ensure that patients in need of post-acute and/or nonurgent care are able to be seen in an outpatient ambulatory setting. The difficulty in obtaining primary care appointments can be alleviated through scheduling models that accommodate same-day appointments and walk-ins and/or have open scheduling. ED SU programs that take over primary care for a specified period of time until behavioral, social, and medical conditions are stabilized will be most effective at reducing the burden on already overwhelmed primary care providers and will ensure than patients receive the most appropriate care when needed. This approach necessitates a thorough handoff between the ambulatory ICU or SU clinic and the patient’s primary care medical home.

Lastly, implementation of a rigorous ED SU program requires the timely and accurate identification of SUs when they arrive in the ED. Because many SUs frequent multiple EDs, accurate information exchange between regional providers is necessary to facilitate optimal care delivery and SU identification. Regional collaboration systems such as EDIE can aggregate patient visit data across multiple EDs and make providers more knowledgeable about when an SU appears in their ED. SU programs that deliver care through a patient’s primary care home or temporarily absorb patients into an ambulatory ICU model can tie funding to their payer and ensure that all treatment is attributed through their “home” care organization.

WHY NOW?

Improving patient outcomes and driving meaningful healthcare access has the potential to significantly impact costs from the perspective of patients, payers, and providers. Nearly 60% of Medicaid beneficiaries who are among the most expensive 10% remain at that percentage for 2 subsequent years,20 further reinforcing the need to break the cycle of super utilization and rapidly develop interventions to care for this high-acuity population.

The movement toward mandatory managed care for both Medicaid and private insurers has accelerated the shift toward value-based reimbursement. As more patients are attributed to specific PCPs and there is continued movement toward value-based payment, physicians will be further incentivized to address their patients’ full spectrum of health needs in low-cost, outpatient settings. Serving patients across the care continuum will necessitate reliance on multidisciplinary care teams and increase the need for nontraditional delivery of care. By addressing the needs of the SU population, providers can make strides toward decreasing the financial impact created by the transition to value-based reimbursement.

Footnotes

1. Christopher Stamy and A. Clinton MacKinney, “Emergency Department Super Utilizer Programs: Rural Health Systems Analysis and Technical Assistance Project,” RUPRI Center for Rural Health Policy Analysis, October 31, 2013.

2. Derek DeLia et al.,”Emergency department utilization and capacity,” The Synthesis Project, July 2009, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22052080

3. Peter Cunningham, “Nonurgent Use of Hospital Emergency Departments,” statement given before the U.S. Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee Subcommittee on Primary Health and Aging, May 11, 2011.

4. Cindy Mann, “Targeting Medicaid Super-Utilizers to Decrease Costs and Improve Quality,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and Department of Health & Human Services, http://www medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/CIB-07-24-2013.pdf.

5. Steven Cohen and Namrata Uberoi, “Differentials in the Concentration in the Level of Health Expenditures across Population Subgroups in the U.S., 2010,” AHRQ, August 2013, http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st421/stat421.shtml.

6. Michael Sandler, “ER visits still rising despite ACA,” Modern Healthcare, January 17, 2015, http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20150117/N…

7. “Emergency Medicine and Payment Reform,” American College of Emergency Physicians, https://www.acep.org/Physician-Resources/Practice-Resources/Administration/Financial-Issues-/- Reimbursement/Emergency-Medicine-and-Payment-Reform.

8. “Reducing Inappropriate Emergency Room Use among Medicaid Recipients By Linking Them to a Regular Source of Care,” The Partnership for Medicaid, http://thepartnershipformedicaid.org/ images/upload/ER_Use-20150702.pdf.

9.Cindy Mann, “Targeting Medicaid Super-Utilizers to Decrease Costs and Improve Quality,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and Department of Health & Human Services, http://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/CIB-07-24-2013.pdf.

10. ibid

11. ibid

12. ibid

13. Health Integration Project: Emergency Department Diversion,” Central Oregon Health Council, June 2011, http://www.apadivisions.org/division-31/news-events/blog/health-care/emergency- departmentdiversion.pd

14. ED Utilization Slides.” St. Charles Medical Center, 2015, unpublished internal document

15. Cindy Mann, “Targeting Medicaid Super-Utilizers to Decrease Costs and Improve Quality,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and Department of Health & Human Services, http://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/CIB-07-24-2013.pdf.

16. Sonya Bethke, “The Coordinated Care Center: An Ambulatory ICU for Complex Patients,” Harvard Business School Open Forum, https://openforum.hbs.org/challenge/hbs-hms-health- accelerationchallenge/innovations/the-coordinated-care-center-an-ambulatory-icu-for-complex-patients

17. Cindy Mann, “Targeting Medicaid Super-Utilizers to Decrease Costs and Improve Quality,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and Department of Health & Human Services, http://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/CIB-07-24-2013.pdf.

18. Reducing Emergency Department Overuse: A $38 Billion Opportunity,” National Priorities Partnership, 2010

19. Cindy Mann, “Targeting Medicaid Super-Utilizers to Decrease Costs and Improve Quality,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and Department of Health & Human Services, http://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/CIB-07-24-2013.pdf.

20. Christopher Stamy and A. Clinton MacKinney, “Emergency Department Super Utilizer Programs: Rural Health Systems Analysis and Technical Assistance Project,” RUPRI Center for Rural Health Policy Analysis, October 31, 2013.