Neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) have long been an essential revenue generator for children’s hospitals, as well as a source of pride for providers and administrators. These units showcase a hospital’s expertise, with highly trained staff, advanced care coordination techniques, and cutting-edge equipment converging to treat the sickest and most vulnerable pediatric patients.

However, as children’s hospitals continue to face increased financial pressure, driven by rising expenses and reduced payments for inpatient services, NICUs can no longer be relied upon to subsidize other services with low or negative margins. Today, to ensure continued financial health and patient satisfaction, hospital leadership must regularly review and adjust NICU processes. This article explores strategies for creating greater efficiencies through changes to staffing models, care coordination processes, and compensation structures. It also provides guidance on developing the cultural foundation necessary to gain key stakeholders’ buy-in as changes to the NICU are identified and implemented.

CHANGING THE STAFFING MODEL

Children’s hospitals need to ensure that unit coverage is adequate, particularly when the patient census in the NICU oscillates. This is challenging in light of the ongoing shortage of neonatologists.1 In response, many NICUs have successfully addressed the more limited physician labor pool by taking greater advantage of advanced practice providers (APPs), specifically neonatal nurse practitioners (NNPs). For example, rather than sending a neonatologist and an NNP to see each patient, some NICUs now make provider assignments based on patient acuity level. NNPs manage low-acuity patients independently, freeing up neonatologists to spend more time with standard-acuity patients. Neonatologists and NNPs remain paired when it comes to the highest-acuity patients. While licensure and billing practices do vary regionally, states have generally shown an increased willingness to expand the scope of practice for APPs, supporting this staffing approach.

Physicians may initially balk at delegating patient care to APPs, especially if they are required to retain medical and legal responsibility over patients. However, the many benefits of allowing NNPs to toggle between collaborative and autonomous work can often calm any uneasiness among physicians. All providers—including APPs—can spend more quality time with their patients when their caseloads are smaller. Workdays not only become more efficient and streamlined, but also more pleasurable as time is freed up for direct patient care.

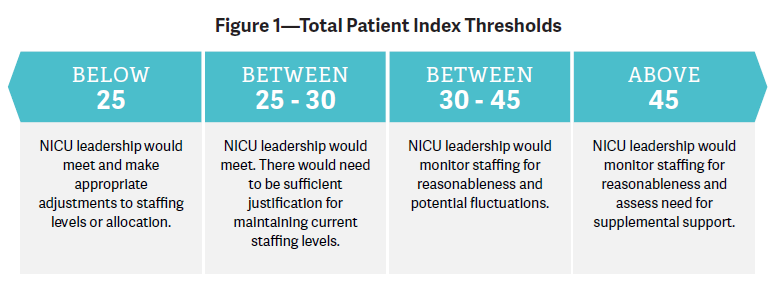

In addition to using a provider mix richer in APPs, organizations will benefit from a flexible staffing model that accounts for fluctuations in the patient census by establishing census volume thresholds that trigger reassessment of staffing levels (see Figure 1). NICUs can also use more complex tools that factor in acuity.

Figure 1. Utilize a tool such as the Total Patient Index as the basis for a flexible staffing model. For a 24-hour period, assess the total patient load by adding the number of admissions and discharges during the period to the current census. In this example, a census above or below the unit average of 30 patients triggers reconsideration of staffing levels.

NICUs that prefer to stick to a fixed staffing model will still benefit from monitoring the census. For example, when the census is low, providers can be directed to activities that contribute to overall unit efficiency, such as catching up on documentation and making discharge follow-up calls.

NNPs and neonatal physician assistants (PAs) are an integral part of our NICU team at Seattle Children’s Hospital and at the four community NICUs where we provide neonatal professional services. Our care model is flexible, depending on the clinical needs of the patient, with sharing of documentation duties. NNPs and PAs independently care for most of our Level II patients and newborns with input from neonatologists only if they ask. We collaboratively admit and care for Level III and IV patients, but the NNPs and PAs independently discharge home all neonatal patients from our community hospitals. This flexibility improves efficiency, increases our time to be with patients and families, and facilitates communication and care coordination—resulting in better outcomes and shorter lengths of stay.

J. CRAIG JACKSON, MD, MHA

Professor of Pediatrics, Division of Neonatology, University of Washington; Associate Division Head, Clinical Strategic Planning, Seattle Children’s Hospital; Medical Director, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Seattle Children’s Hospital

IMPROVING CARE COORDINATION

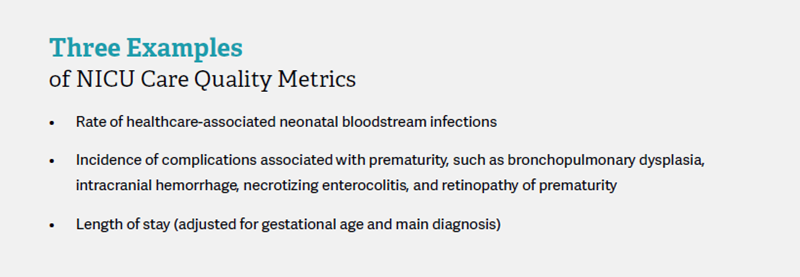

Across the board, providers and administrators alike recognize care coordination as mission-critical to the NICU, resulting in increased efficiencies and greater patient family satisfaction. Coverage in the NICU presents complex care coordination challenges, including multiple provider handoffs, specialist referrals, family touch points, proper management of lengths of stay, and patient transitions back into the home setting. Hospitals across the industry are increasingly focused on introducing tools and strategies to streamline these complex aspects of care and to standardize care among providers. As a response to this movement, The Joint Commission and Vermont Oxford have developed quality measures such as case-based length of stay to help quantify and standardize care across the industry and to enable organizations to benchmark their performance.

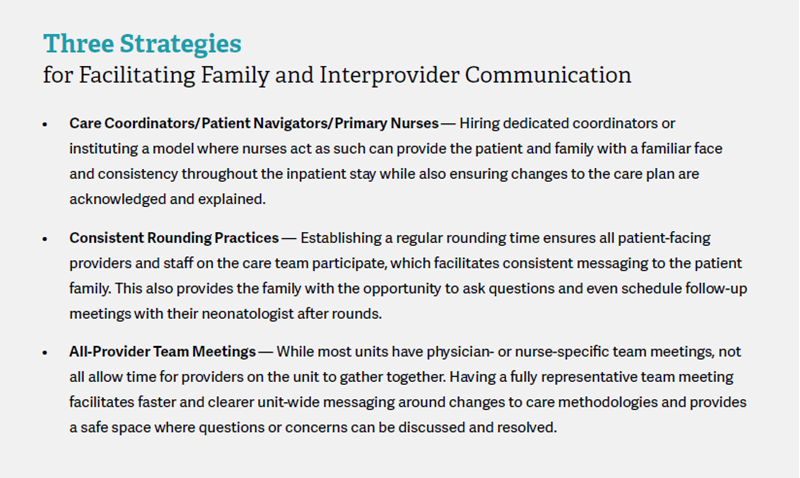

In addition to the logistical aspects of care coordination, there is also a communication component, both between providers and with the emotionally vulnerable families of their patients. Providers must delicately balance managing expectations, explaining evolutions in the care plan, and engendering a spirit of involvement with the family. This is not simply ideal but rather necessary, as there is a strong correlation between consistency and quality of provider communication and patient satisfaction.2

Improving communication is a key aspect of our approach to care coordination at Blank Children’s. The creation of an organizational framework for optimizing interprovider communication is essential to achieving clinical efficiency and the best family experience in our NICU.

BECKY PATTON-QUIGLEY, CAPPM, MCPM

Administrative Director, Blank Children’s Hospital

LEVERAGING CREATIVE COMPENSATION MODELS

Compensation methodologies for pediatric inpatient units continue to evolve across the industry to better reflect the full scope of services provided by clinicians. Work relative value units (WRVUs) or shifts worked remain the most common basis for variable compensation models, but they fail to capture the full extent of NICU provider responsibilities, including administrative, quality improvement, and care management duties. Hospital and physician group administrators are looking at creative approaches to variable compensation structures based on metrics like patient satisfaction, which can be measured through surveys or discharge follow-up calls, and quality of care.

In addition, innovative incentives are increasingly tied to the concept of “citizenship,” measured by tracking participation in physician councils and community outreach and education programs. Peer-to-peer rating systems can also be effective in ensuring the level of respect, collegiality, and trust necessary for units to operate collaboratively and at peak efficiency.

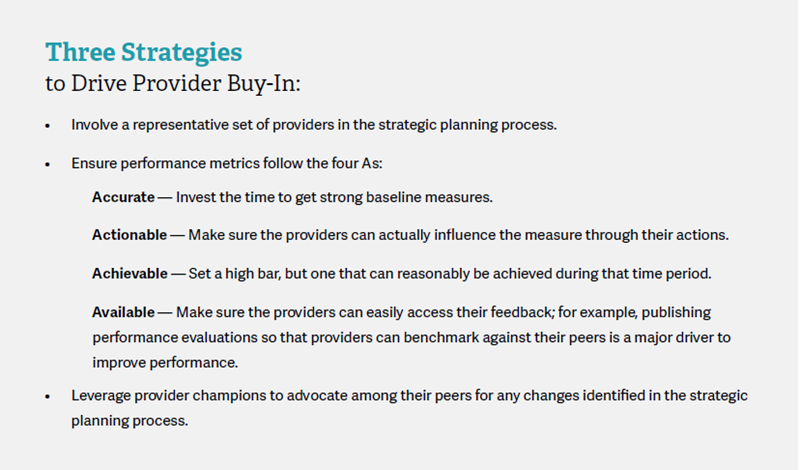

Regardless of the incentive, providers need to be included in discussions about variable compensation. If they have a sense of ownership and control over new approaches, they will be actively engaged and more open to these innovative models. If they are not included in these discussions, it is likely they will simply find a way to “manage to the metric,” which stymies the true impact of these changes.

NURTURING A CULTURE OF CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT

The success of all of these recommendations—in fact, of any major operational change in a NICU—hinges on an organizational culture that embraces continuous improvement. Without that foundation, it is difficult if not impossible to obtain buy-in from key stakeholders. Moreover, making the NICU more efficient is not a onetime initiative, but rather an ongoing endeavor. Implementing new staffing models, introducing variable compensation, and improving care coordination are each major undertakings that take time and sustained effort. Organizations also need to be willing to revisit their initial approaches in a healthcare environment that is constantly changing. Establishing a collaborative culture dedicated to improvement primes stakeholders for change and helps overcome resistance to new initiatives.

Provider Buy-In

Shared ownership is an essential component to creating a lasting culture of continuous improvement, so organizations should have strategies in place to align their NICU providers (physicians and APPs). In fact, even in organizations with cultures that truly embrace continuous improvement, providers and administrators may bristle when their clinical and operational practices are scrutinized.

KEY TAKEAWAYS FOR THE NICU

Amid increased pressure on children’s hospitals to contain costs, hospital leaders are bringing more intense financial and operational scrutiny to the NICU setting. To ensure continued profitability, hospitals must engage in strategic planning, reviewing NICU processes with a critical eye. Recommendations include moving to a more flexible staffing model, building communication processes that enhance care coordination, and introducing quality-oriented compensation structures. These changes serve the dual purpose of driving down costs and enhancing patient outcomes and experience.

Footnotes

1. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2013 to 2025, Association of American Medical Colleges, March 2015 (https://www.aamc.org/

download/426242/data/ihsreportdownload.pdf?cm_mmc=AAMC-_-ScientificAffairs-_-PDF-_-ihsreport).

2. Parent Satisfaction With Communication Is Associated With Physician’s Patient-Centered Communication Patterns During Family Conferences, Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, April 7, 2016 (http://journals.lww.com/pccmjournal/Abstract/publishahead/Parent_Satisfaction_With_Communication_Is.98839.aspx).