It’s that time of year again—resident recruiting season. Whenever residency programs receive applications from prospective trainees, our clients ask how they should gather and validate applicant-provided information that can help them with future resident onboarding. Recently, we completed a study on behalf of a client in which we reviewed regulatory and accreditation requirements, researched best practices, described legal ramifications, and formulated recommendations on this very topic. This article shares learnings emanating from that work with the broader GME community and explains the benefits associated with fully credentialing residents and fellows.

Why Is There So Much Variation?

There is wide variation in the sophistication and execution of resident credentialing processes in teaching hospitals. Many factors contribute to this lack of consistency, including differing interpretations of requirements, lack of coordination between the GME office and medical staff office, and lack of resources/staff dedicated to the credentialing of residents. But the biggest driver of inconsistency is the limited guidance from accrediting bodies concerning how to manage and document information. The ACGME, CODA, and CPME require GME programs to define criteria for resident and fellow participation in the respective training programs (e.g., documentation of graduation from an approved undergraduate educational program, state licensure) but offer little in terms of concrete instructions on how best to collect and store data on resident qualifications. [1] , [2] , [3]

To complicate matters further, residents in accredited programs train under the supervision of attending physicians. Therefore, in the strictest sense, residents are not independent practitioners; as such, they are often not credentialed through the medical staff process. That’s not to say all trainees are not fully credentialed. There are circumstances that necessitate full credentialing of residents:

- Residents working outside of their training program in a paid position (i.e., “moonlighting”)

- Residents in training programs that are not accredited by a CMS-recognized accrediting agency [For the purposes of this discussion, “CMS-recognized accrediting agency” refers to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), American Osteopathic Association, Council on Podiatric Medical Education (CPME), and/or Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA). We recognize that hospitals may offer subspecialty training approved by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) or other specialty boards. While such programs may be eligible for Medicare reimbursement, for the purposes of this discussion, they are categorized as nonaccredited.]

- Subspecialty residents (i.e., fellows) practicing and billing independently for services outside the scope of their training programs

As a result, it is easy to imagine a scenario in which a teaching hospital has gathered and verified sufficient information to fully credential some residents and fellows but not others. This exposes the hospital to risk. The greatest risks, of course, are to patient safety, but there are also legal, fiscal, and operational implications associated with inconsistent credentialing practices that would impact both the residency program and the hospital as a whole if left unchecked. Given the integral role residents play in patient care teams and the hospital’s substantial investment in its GME programs, it is prudent to protect the time, energy, and resources allocated to the teaching programs by evaluating the hospital’s credentialing practices proactively rather than assuming nothing bad will happen.

What Are the Risks?

There have been several court cases in which hospitals and health systems were found liable for the actions of physicians on their medical staff due to negligent credentialing practices. Table 1 provides a representative sample of signature cases. In particular, courts have held that hospitals can’t use lack of information about a physician as a rationale or defense against legal claims. Many of these cases involve independently practicing physicians; however, there is legal precedence related to negligent credentialing that presumably could be applied to residents or fellows.

|

Case |

Implications |

|

| |

|

First case in the country to apply the corporate negligence doctrine; the hospital was found financially liable for damages due to the physician’s action. | |

|

Johnson v. Misericordia Community Hospital (1981)[5] |

Court held that the hospital contributed to the patient’s injury by failing to verify the physician’s previous malpractice cases and employment history. |

|

Elam v. College Park Hospital (1982)[6] |

Court held that the hospital is financially liable for a podiatrist’s negligence for failing to obtain previous malpractice claims data; the hospital has a duty to select and review staff physicians. |

|

Bell v. Sharp Cabrillo Hospital (1989)[6] |

Court held that the hospital was financially liable for the physician’s actions due to its failure to request data from a previous employer about its basis for summary suspension of the physician’s privileges. |

|

| |

|

Kadlec Medical Center v. Lakeview Anesthesia Associates (2006)[7] |

Kadlec was sued for negligence of one of its physicians and settled for $7.5 million. Subsequently, Kadlec was awarded $8.2 million in damages by the Louisiana District Court because the defendants failed to provide an accurate report of this former employed physician. |

|

Estate of Fazaldin v. Englewood Hospital & Medical Center (2007)[7] |

Court held that the hospital had a legal duty to report its termination of physician employment to state and federal data banks to protect future employers and patients. |

|

Frigo v. Silver Cross Hospital and Medical Center (2007)[4],[7] |

Court held that the hospital was responsible for $7.8 million in damages because the patient’s injury would not have been caused had the hospital not issued privileges to the physician. |

|

Larson v. Wasemiller (2007)[4] |

Court recognized negligent credentialing as a valid claim; in the opinion it rendered, the court cited that 30 other states recognize this tort theory. |

|

Court recognized negligent credentialing as a valid claim; the hospital was held responsible for damages. | |

|

Various Plaintiffs v. Allen Sossan, MD, Mercy Health Avera Sacred Heart, and Lewis and Clark Specialty Hospital (2015)[9],[10] |

Court recognized negligent credentialing as a valid claim; the case named more than a dozen physicians who served on the committees that approved surgical privileges for a spine surgeon at the hospitals co-named in the suit. Plaintiffs claimed that the surgeon was credentialed even though the medical community knew he had lost credentials at a hospital in another state and lied on his medical license application; suits settled for an undisclosed amount. |

|

| |

|

Juli Treadwell and Bryan Steinborn on behalf of the Estate of Olivia Steinborn, v. Excel ER, LLC d/b/a Excel ER Keller and Brandon Baker Morshedi, MD (2017)[11] |

Freestanding emergency department accused of failing to staff appropriately qualified and experienced physicians and not disclosing the credentials and training status of residents providing clinical coverage. |

|

Various Plaintiffs v. William Husel, MD, Mount Carmel Health System, and Trinity Health (2019)[12] |

Physician criminally charged with murder and multiple wrongful death suits, which name the physician, hospital, and its parent company; whistleblower reported that the physician did not meet the hospital’s requirements to work as a critical care intensivist but was hired and received privileges anyway; the hospital has paid more than $13 million in claims to date. |

The decisions in these cases support the principle that hospitals and health systems are responsible for ensuring the quality of care provided to patients, which extends to verifying the credentials of physicians on the medical staff and providing general medical staff oversight. Additionally, a recent article in JAMA Surgery reviewed medical malpractice lawsuits involving medical residents and found that while hospitals and supervising faculty are more often the parties named in lawsuits, litigation filed directly against residents can still be costly for teaching hospitals.[13]

GME Credentialing Approaches

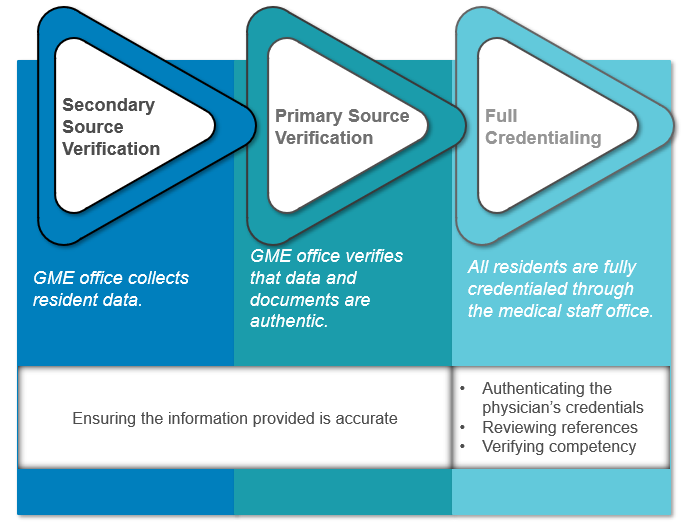

Several options exist for credentialing residents who are engaged exclusively in training. Three common models are illustrated in figure 1. [Although not discussed here, teaching hospitals may also consider developing policies to address the verification of credentials for other trainees as well (e.g., pharmacy residents, medical students, nursing and other allied health students).]

In reviewing these models, it is important to distinguish between “verification of credentials” and “credentialing”:

- Verification of credentials refers to the process of authenticating credentials (i.e., ensuring that the information provided is accurate).

- Credentialing is broader and includes the overall process of authenticating credentials, reviewing references, and verifying competency; the results of this review dictate whether the applicant is granted medical staff membership and hospital privileges.

Secondary Source Verification

Under this model, the teaching hospital typically relies on resident-provided information from the Electronic Residency Application Service. While this approach requires limited hospital resources (i.e., personnel time to gather and validate data), there is a potential risk for incomplete or outdated information, falsification, and/or misrepresentation. Furthermore, the hospital has inconsistent levels of information about physicians practicing in the facility (e.g., residents and attending physicians are not subject to the same standards). This makes it difficult to communicate practice guidelines and supervision policies to other team members.

Primary Source Verification

Teaching hospitals requiring primary source verification collect certified documentation (e.g., directly from medical schools) to validate educational and employment history. Data verification may be the responsibility of the GME office and/or the medical staff office. Roles and responsibilities must be clearly defined and articulated. This approach minimizes the opportunity for misrepresentation or falsification of data but is more time consuming than secondary source verification and still leaves the hospital with inconsistent levels of physician information.

Full Credentialing

Full credentialing includes increased coordination between the GME office and the medical staff office, which facilitates awareness of all GME training occurring within the facility. Residents are subject to the same credentialing policies and processes as the medical staff, effectively eliminating the opportunity for falsification or misrepresentation and ensuring the equal and consistent application of standards for all physicians, including residents and attendings. On average, this requires about 20 hours of effort per provider.[14] This approach also allows for more efficient and standardized onboarding of residents who join the medical staff upon graduation because their information has already been gathered and validated, meaning they can begin billing and collecting professional fee revenue more quickly. This model is the most resource intensive, and medical staff bylaws may need to be updated to include provisions related to residents. Based on a review of publicly available information on hospital credentialing requirements, it appears few teaching hospitals pursue this option.

Confidence Outweighs Cost

Fully credentialing residents is the most conservative—and costly—approach to documenting the qualifications of physician trainees. But it is also the most comprehensive, and it gives hospital leaders the most information and the greatest level of certainty that the physicians practicing in their facility have been adequately vetted and their patients are safe.

Although fully credentialing residents requires an investment of time, staff, and other resources, hospitals may be able to optimize their current credentialing process and use existing resources to support efforts to credential residents. It may also be possible to centralize and standardize the resident credentialing process in multihospital systems and among partners or outsource credentialing responsibilities to a professional vendor. In time, the return on investment should be evident in the faster processing and onboarding of graduating residents and the greater level of comfort with the knowledge that risks associated with inconsistent information have been minimized. The benefits—especially ensuring the safety of patients—far outweigh the costs that may arise if problems occur.

Footnotes

1. ACGME common program requirements (residency). ACGME.org. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2019.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2020.

2. Accreditation standards for advanced education programs in general dentistry. ADA.org. http://www.ada.org/~/media/CODA/Files/aegd.ashx. Accessed June 16, 2020.

3. Standards and requirements for approval of podiatric medicine and surgery residents.CPME.org.

4. Callahan, M. Negligent credentialing developments: impact of recent cases and new Joint Commission medical staff standards. Katten.com.

5. Watkins, A., 2005. Negligent Credentialing Lawsuits. Marblehead, MA: HCPro.

6. Lambert-Gale, A. Importance of credentialing. Slideplayer.com. https://slideplayer.com/slide/3586450/. Accessed October 21, 2016.

7. Fontenot, S. Health law and regulations. ACHE.org. Accessed October 21, 2016.

8. Lambert-Gale, A. Importance of credentialing. Slideplayer.com. https://slideplayer.com/slide/3586450/. Accessed October 21, 2016.

9. Ellis, J. Ruling opens hospitals to lawsuits. Argusleader.com. https://www.argusleader.com/story/blogs/jonathanellis/2015/10/26/ruling-opens-hospitals-lawsuits/74651222. Published October 26, 2015. Accessed June 16, 2020.

10. Dyrda, L. Lawsuits against fugitive neurosurgeon Dr. Allen Sossan settled. Beckersspine.com. https://www.beckersspine.com/spine/item/47574-lawsuits-against-fugitive-neurosurgeon-dr-allen-sossan-settled.html. Published November 22, 2019. Accessed June 16, 2020.

11. Gibb, G. First responder medical malpractice lawsuit in Texas seeks $1 million. Lawyersand settlements.com. https://www.lawyersandsettlements.com/legal-news/first-responders-malpractice/first-responder-malpractice-lawsuit-22707.html. Published November 11, 2017. Accessed June 16, 2020.

12. Haeberle, B. Whistleblower: Husel did not meet criteria to work in Mount Carmel ICU. 10tv.com. https://www.10tv.com/article/news/investigations/10-investigates/whistleblower-husel-did-not-meet-criteria-work-mount-carmel-icu-2019-may/530-0b884386-7f56-4495-824b-fd28e8087508. Published May 2, 2019. Accessed June 16, 2020.

13. Thiels, C., Choudhry, A., Ray-Zack, M., Lindor, R., Bergquist, J., Habermann, E. and Zielinski, M., 2018. Medical Malpractice Lawsuits Involving Surgical Residents. JAMA Surgery, 153(1), p.8.

14. Kleinstreuer, J. Why does credentialing take so long and cost so much? Intivahealth.com https://intivahealth.com/blog/why-does-credentialing-take-so-long. Published August 7, 2019. Accessed June 25, 2020.